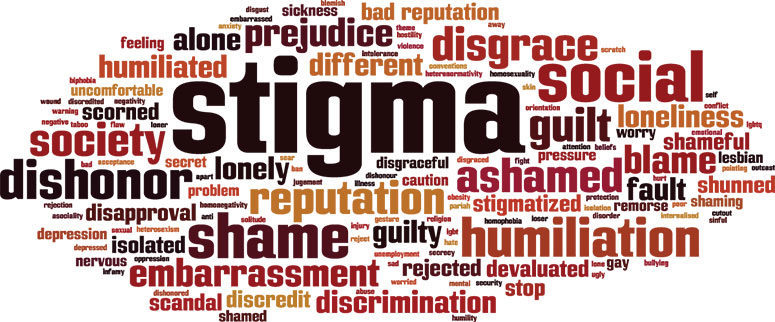

Addiction, a pervasive issue in our society, often presents a myriad of challenges that are amplified by the stigma associated with it. This stigma, a blend of misunderstanding, judgment, and discrimination, creates significant hurdles for individuals wrestling with substance use disorder. Our focus in this article is to scrutinize the stigma of addiction – its origins, effects, and the urgent need for a societal shift towards empathy and understanding.

The stigma surrounding addiction can be damaging to individuals who are struggling with substance abuse. When you admit that you have an addiction, or people find out publicly, they may praise you for your bravery. This suggests that society expects people with addiction to feel shame about their condition.

Understanding Addiction

At its core, addiction is a chronic brain disease characterized by compulsive substance use despite harmful consequences. It involves alterations in the brain’s reward, motivation, memory, and related circuitry, leading to dysfunctional emotional responses and behaviors. Substance use disorders encompass a range of conditions, including drug addiction, alcohol use disorder, and opioid use disorder, to name a few.

Contrary to common belief, addiction is not a moral failing or a choice, but a health condition that requires comprehensive care and support. It doesn’t discriminate, affecting people across all socioeconomic strata, and it’s not a condition that one can simply “snap out of.”

The Stigma of Addiction: Its Origins and Impact

The stigma surrounding addiction is deep-rooted and multifaceted, often painting those suffering from substance use disorder as morally deficient, weak-willed, or dangerous. This stigma is fueled by misconceptions, fear, and a lack of understanding about the nature of addiction.

The repercussions of this stigma are profound, often creating barriers to seeking help and accessing vital mental health services. Individuals struggling with addiction may internalize the stigma, leading to feelings of shame, guilt, and isolation – a phenomenon known as self-stigma. These feelings can exacerbate mental health conditions and deter individuals from seeking help, thereby perpetuating a vicious cycle.

Moreover, the stigma extends into the healthcare system, where healthcare providers may inadvertently harbor biases, leading to substandard care. It also impacts the individuals’ loved ones and complicates their ability to provide the necessary support.

The stigma of addiction is one that is often seen in society. People who are addicted to drugs or alcohol are often seen as bad people, and they are often looked down upon. This is a shame, because addiction is a disease, and those who are addicted should be treated with compassion.

Addiction is a disease that can affect anyone. It does not discriminate, and it does not care about your social status or your income. Addiction can affect anyone, and it can ruin lives.

The stigma of addiction needs to be eliminated. Those who are addicted should be treated with compassion and understanding, and they should not be ashamed or embarrassed. Addiction is a disease, and it should be treated as such.

The Repercussions Of Stigmas Surrounding Addiction

| Effects of Stigma on Individuals with Substance Use Disorder | Effects of Stigma on Families of Individuals with Substance Use Disorder |

|---|---|

| Internalized shame and guilt | Increased stress and emotional burden |

| Low self-esteem and self-worth | Social isolation and withdrawal |

| Reluctance to seek help and treatment | Fear of judgment and discrimination |

| Limited access to healthcare and support services | Financial strain and economic hardships |

| Discrimination in employment and housing | Impaired family dynamics and strained relationships |

| Reduced opportunities for education and employment | Increased caregiver responsibilities and burnout |

| Negative impact on mental health and well-being | Uncertainty and fear for the safety and well-being of the loved one |

| Higher risk of relapse due to lack of support and stigma-related stress | Emotional and psychological distress |

High Functioning Addicts And Professional Stigma

The stigma associated with drug and alcohol addiction continues to pose significant barriers, particularly among professionals. Many perceive addiction as a character flaw or a sign of weak willpower rather than a recognized medical condition. This judgment often inhibits those who are struggling from seeking help due to fear of career implications, professional ridicule, or damage to their reputation. Additionally, workplace cultures that stigmatize addiction can lead to discrimination, further isolating affected individuals and discouraging them from pursuing recovery. It’s crucial to acknowledge and address these stigmas to create safer, more supportive environments that promote understanding, acceptance, and timely intervention for professionals struggling with substance abuse issues.

How Do You Reduce The Stigma Of Addiction?

Addiction is a disease that can affect anyone. It is important to remember that addiction is not a choice, and those who are struggling with addiction should be given support and compassion. There are many ways to reduce the stigma of addiction, including education and open conversation. It is important to talk openly about addiction and dispel the myths and stereotypes that surround it. We can also challenge the negative attitudes and beliefs that contribute to the stigma of addiction. By working together, we can create a society where those affected by addiction are treated with understanding and respect.

Addiction Is A Disease

According to the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 15.1 million adults ages 18 and older had Alcohol Use Disorder, including 9.8 million men and 5.3 million women.*If you catch yourself judging others for their drinking and drug use, consider this. Would you blame someone for having cancer, or having some other affliction? There are some things in this life we have no control over. However, we do have choices of how we respond to the truth of our condition, once we are ready to hear it.

The mentality and behavior of drug addicts and alcoholics are wholly irrational until you understand that they are completely powerless over their addiction and unless they have structured help, they have no hope.

Reducing the Stigma: A Societal Imperative

Eradicating the stigma of addiction is a collective responsibility that requires concerted efforts from all sectors of society. These efforts include:

1. Education: Public awareness campaigns and educational initiatives can dispel myths about addiction, foster empathy, and promote a more accurate understanding of substance use disorders.

2. Language: Words matter. Using person-first language (e.g., “person with a substance use disorder” rather than “substance abuser”) can help reduce the dehumanization and judgment associated with addiction.

3. Policies: Implementing fair policies and laws that protect people with substance use disorder from discrimination is crucial. Moreover, enhancing the availability and accessibility of mental health services can ensure that those affected receive the help they need.

4. Advocacy: Promoting stories of recovery, emphasizing the capability of individuals with substance use disorder to lead fulfilling lives, can challenge stereotypes and inspire hope.

Empowering Recovery and Support for Substance Use Disorder

Overcoming addiction and the associated stigmas can be a challenging journey, but there are numerous resources available for individuals and their loved ones who are actively struggling with substance use disorder. Treatment options such as inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation programs, therapy, and medication-assisted treatment have proven effective in helping individuals break free from the grips of addiction. Furthermore, support groups and mutual aid societies like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) provide a vital network of understanding peers who have walked a similar path. For loved ones, Al-Anon and Nar-Anon offer support groups specifically designed to address the unique challenges faced by families and friends of individuals with addiction. It’s important to recognize that addiction is a medical condition, and seeking help is not a sign of weakness but a courageous step toward recovery. By accessing these resources and fostering a culture of empathy and understanding, we can dismantle the stigmas surrounding addiction and empower individuals and their support systems to embark on a transformative journey of healing.

Final Thoughts On The Stigmas of Addiction

Substance use disorders are a pressing health issue, affecting millions of individuals worldwide. As we strive to combat the devastating effects of addiction, dismantling the stigma is paramount. By fostering a compassionate, understanding, and supportive societal environment, we can aid the recovery process and affirm the inherent worth and dignity of people with substance use disorders. In doing so, we move closer to a society where addiction is recognized not as a mark of shame, but as a condition deserving of care, empathy, and understanding. Contact us today for more information about the detox program and inpatient rehab center in Cincinnati.

The Ridge: Recovery for Life

It’s time for change.

(513) 457-7963

Sources:

- DrugAbuse.com: “The Stigma of Addiction: How It Affects the Sufferer and the Community.” DrugAbuse.com. Accessed May 28, 2023. Link

- Johns Hopkins Medicine: “The Stigma of Addiction.” Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed May 28, 2023. Link

- Quinn, Patrick D., and Miles F. Wilkinson. “The Stigma of Addiction.” Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews, vol. 46, no. 10, 2021, pp. 2003-2004. doi:10.1038/s41386-021-01069-4. Link

- Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 46, Issue 2, March-April 2011, https://academic.oup.com/alcalc/article/46/2/105/198339

- The Stigma That Undermines Care, American Psychological Association, June 2019, https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/06/cover-opioids-stigma

- National institute Of Alcoholism Abuse and Alcoholism Alcohol’s Effects on Health Research-based information on drinking and its impact. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-facts-and-statistics